Writing Process 16

Scintillating Syntax: Part One

‘How do I know what I

mean till I see what I say?’

In earlier Newsletters

here I recommend that you should forge ahead with your narrative, trusting your

intuition and your innate linguistic ability to say what you think and feel.

There comes a point – possibly we have finished the story, or we are a

good half or three quarters of the way through - when we all pause and look at

what we had written in a more objective way. Clearly this is part of the creative editing process.

This is when we come to marvellous issue of

scintillating syntax.

Just as oral storytellers naturally speak in paragraphs and dialogue, we who write our

stories down have this facility at our fingertips. In a post in 2013 I told the

story of how I discovered that I was using syntax in my writing before I knew just what syntax was.

Here’s how it happened

'[…] When I was

in my second year at grammar school, aged twelve, I handed in a composition (called now a piece of creative writing…) called The Fox. My English teacher - a

magisterial, handsome figure of a man - returned my story to me with a high

mark. I treasured this, having learned very quickly the high gold-standard

currency of high marks in that school.

But much

more important, in the margin he’d written in his fine, flowing hand ‘Good Syntax!’

So, what was this thing I was good

at?

I hod never

heard this word before. I daren’t ask my teacher. I had to go to th ebig doctionary, one of the two big books in the house.

There I read:

Syntax

·

The

study of the rules whereby words or other elements of sentence structure are

combined to form grammatical sentences

·

The

pattern of formation of sentences or phrases in a language

·

A

systematic, orderly arrangement of words

So, it

seemed, this is what I was good at!

I was very

pleased by this revelation that I had, unknowingly, been good at this thing

called Syntax.

I reckon that was the point when I actually decided I could be a writer, even though I’d never met a

writer and had actually never met anyone (except my teachers) who wore a white - not a blue - collar to work.

|

More books now... |

The rules of

good syntax were only peripherally taught at that school; despite the fact that

it was called a grammar school. There I only really learned the nature of

syntax and grammar when I started to study French and German. I had to do

this in order to get to grips with languages whose grammatical structures were

different from (different to?) my

own. I still remember the exotic feeling of getting to grips with the subjunctive form in French and than

realising that the subjunctive form

exists in English. I had been using it for years and never realised it.

So how, you might say, did this

little girl who lived in a small crowded house that had only two big books on

its shelves get be the mistress of very good syntax at twelve?

I now feel certain

that reading all kinds of material voraciously when young is the key to the

high literacy necessary if you are to be a writer. This visual, aural and

intellectual process embeds grammar and syntax deep in your psyche – to become available

to you when you need it to write your own stories. This is so even when you

have not articulated the fact that you are using them. It is initially an

unconscious process.

Proper language is already there, deep

inside. I well remember a child in a

class I was teaching, saying to me ‘You mean I already talk in grammar, miss?’

Early in my

studies for teaching career I remember reading that by the age of five

normal children child will have incorporated into their individual brain

structure all the rules of grammar of their own language. Children don’t have

to learn it, they speak it, they talk it, they dream in it. It may later be useful for them to learn the

rules they already operate at some later point - for example when they learn a

foreign language. Or when they so a linguistics or literature degrees.

And of

course we know it is useful when you

become a writer and have to edit your own work…

I know from my workshops

that some writers get jumpy and defensive about grammar and syntax.

Either

they’re hide-bound by the memory of an opinionated or aggressive teach or a

clumsy editor. Or they are terrified of looking stupid. Or - however good a storyteller

they are - they are innocent of grammatical conventions in written

language and fear that very innocence could send their work flying onto some

editor’s floor.

This is a pity -these natural

storytellers can make very good fiction writers. They have the most important

qualities - a feeling for the trajectory of a story, an ear for dialogue and a

fresh world view.

Good,

self-developing writers such as readers here will appraise and creatively edit their own writing,

and recognise the syntactical virtues of their own prose, eventually

incorporating more of the magic of Scintillating Syntax, absorbing it and

incorporating it into their own intuitive prose writing.[...]'

If you are becoming fascinated by the formal intricacies of our own language you might like my

2009 post on The Semi Colon. Also remember Strunk & White's Elements of Style, the simplest reference for issues of grammar and syntax

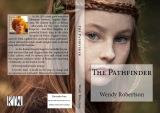

A later

note: These points above have been

enhanced by my experience in writing my newest novel The Pathfinder, where the main thrust of my research was

into the non-literal, artistic, complex, story telling culture of the Celts of West Britain, surviving

under the literate dominant culture of the Romans in the dying stages of their

Empire.

This extract might go towards explaining it.

‘[…] That

was the time my father went on to tell Pendragon and his listeners of a dream

he’d had the previous night, where plucky battles and heroic charges were

replaced by circuses of talk and the exchange of great ideas and of fine and

necessary goods.

'This was in a golden, happy place, where words sustained more benefit than rattling swords,’ he says. ‘And when I awoke, I realised that this is the pathway we should take ourselves. We’re half way there after all. Haven’t we always by custom welcomed into our halls strangers who are storytellers, music-makers and craftsmen? On the other hand, don’t we make warriors – high and low – wait at our gate?’ Because surely it’s talk and exchange that keeps the peace, not battle.’[…]

'This was in a golden, happy place, where words sustained more benefit than rattling swords,’ he says. ‘And when I awoke, I realised that this is the pathway we should take ourselves. We’re half way there after all. Haven’t we always by custom welcomed into our halls strangers who are storytellers, music-makers and craftsmen? On the other hand, don’t we make warriors – high and low – wait at our gate?’ Because surely it’s talk and exchange that keeps the peace, not battle.’[…]

Next Week: Newsletter 17

Scintillating

Syntax Two: Long and Short Sentences.

No comments:

Post a Comment