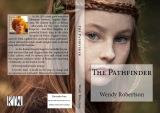

The Writing Process

Newsletters 17 & 18

(NB.Two

in one week as I am off to write and draw in France for

three weeks).

Building Block or Stumbling Block?

Despite my enthusiasm last week about

good syntax I do realise that an over-awareness of the significance

of syntax can be a stumbling block. This happens when you - the newish writer - perhaps because of an officious schoolteacher

school or a clumsy and thoughtless

editor – become frozen, like a rabbit in headlights, at the embarrassment of

being seen as stupid when at first you don’t quite get the difference – for instance

- between verbal storytelling and storytelling

on the page.

There were times when editors would

work with very promising writers who were not quite there in terms of their

syntactical skills. But nowadays they are very busy – even exhausted - with their corporate strategies and business models.

So you

have to do so much more of it yourself!

The point is, you shouldn’t let this

part of writing your story be a stumbling block for you. If you edit

yourself with a more certain knowledge of syntax, the manuscript you present to

others for appraisal or publication will not have laughable flaws that could

blind the readers to a wonderful story.

This process of ultimate self-editing

is even more crucial in these days of indie publishing and eBooking. One

of the biggest criticisms of the contemporary flood of self-published eBooks is

the variable standard of editing without the filter of a tribe of publisher’s

editors to catch the flaws.

You should realise that, while attending closely to your own syntax can be intricate, in the end it is relatively easy and - dare I say it? - it is fun. Every writer should be the master of his or her own language. Grammar stands there alongside originality, vision, vocabulary, narrative skill as a crucial tool for the successful writer, whatever their approach to publishing.

Focusing on Valuable Building Blocks

The first crucial

building block for a you as a writer is your ability to create a world, to

build a narrative, to have an extensive vocabulary (all that reading!) and a

mind that sees the world afresh –dreaming dreams and having visions.

A second building block consists

of your innate sense of story imbued with the magic of your own unique sense of

language so that you become comfortable when you get to the stage of completing

your initial charge of pure creative writing and reach the point when you start

editing your own work. Here, as I have been saying I reckon there is value in

seeing your own prose more objectively in terms of your unique use of grammar

and syntax

Once you begin to know just how the

rules of syntax work then you can choose, if you want, to break them. But that

will then be a knowing process. You will

know what you are doing.

And, as you

clarify and edit your own prose, as a natural writer and a good storyteller you

can comfort yourself in knowing that there are some individuals out there who

know syntax up to their eyeballs but could never pen an original, good story in

a hundred years.

Let’s have a quick look at some basics to start out on this

process.

In my workshops, when

they begin to trust that I won’t laugh at their innocence, some new writers will

ask crucial questions what seem to be the arcane mysteries of grammar and syntax and these questions are

the key to their further writing development.

Among these questions will be:

1. Just what is that makes a proper

sentence a sentence?

2. What is it that constitutes a

paragraph?

3. What’s the difference between

dialogue told and dialogue said?

For the Record: A

Simple Definition: A sentence expresses a complete

thought and must contain at least a subject (a noun) and (a verb). A sentence begins with a capital letter and ends

with a full stop, a question mark or an exclamation mark.

Click HERE for a good

place to explore further the grammatical nature of sentences, paragraphs and

dialogue

A Quick Thought about Paragraphs

The rules on paragraphing

can be ambiguous. I suggest that a paragraph is a whole idea, a piece of speech

or an aspect of the whole setting, building up the climax of the narrative

within the chapter or the short story. It promotes the transparency of the

narrative. It does not get between the reader and the narrative.

Look at the paragraphing on any page. Notice that white space on

the page promotes space and clarity; it allows the reader to breathe his own

way into your narrative.

Top tip. When the idea, the speaker, the setting changes, embark on a new

paragraph.

Ursula le Guin on The Significance of Sentences

The other day I was reading again

Ursula le Guin’s seminal ‘Steering the

Craft’. I was excited again when I came across her chapter Sentence Length and Complex Syntax.

|

Click Ursula |

In this chapter, among other wise advice, Le Guin comments:

The basic function of the narrative sentence is to keep the

story going and keep the reader going with it.

And

But for the most part, prose states its proper beauty and

power deeper, hiding it in the work as a whole.

It is a creative writing truism that modern

prose tends towards the greater use of shorter, more journalistic sentences to

roll a story on faster, in the manner of a film, flashing from scene to scene.

This could be how your ‘hear’ your story as you are writing it. It will have an

effect on your writing style. It’s useful to be conscious of this as you are

editing your own work.

However

in her compelling chapter Le Guin recommends a combination of short and long

sentences for the most successful prose:

‘To avoid long sentences and the

marvellously supple connections of complex syntax it to deprive your prose of

an essential quality. Commenctedness is what keeps a narrative going.’

In the chapter she quotes examples

from a wide field of writers who use the balance of long and short sentences: Jane Austen; Harriet Beecher Stowe; Mark Twin;

Virginia Woolf

Best Advice

It’s not a bad idea to

read two pages of their work and note what how grammar and syntax works in the

case of these great writers – and of any great modern writers whom you admire.

For me, page-long paragraphs –

acceptable in nineteenth century and early twentieth century novels - will

give a modern novel a dated feel. Language and grammar are dynamic forces in

prose; they change through time. They evolve.

One evolution is the way some

writers may have a very clean and naturalistic almost film script way to

present dialogue which can make. This can make some purists tut-tut. Modern writers are making their own choices. So

now you as a writer can break the rules in this evolving form, as you look for

the best way to engage your readers, make them commit to your narrative.

As always my very best advice is to read more, and more regularly - both classic modern well-written novels. With your writer’s cloak on you can look at how sentences, paragraphs and dialogue presents themselves on the pages of modern novels and short stories.

**********************************************

Newsletter 18

Why does Syntax become a Stumbling Block?

This happens when you –

perhaps from school or a clumsy and thoughtless editor – become frozen like a

rabbit in headlights at the embarrassment of being seen as stupid when you

don’t quite get the difference between verbal storytelling and storytelling on

the page.

At one time editors would work with

very promising writers who were not quite there. But nowadays they are very

busy, exhausted with their corporate strategies and business models, so you

have to do it yourself,

So don’t let syntax

be a stumbling block. If you edit yourself with a clear knowledge of

syntax the manuscript you present will not have laughable flaws that could

blind the readers to a wonderful story.

This assiduous process of

ultimate self-editing is even more crucial in these days of indie

publishing and eBooking. One of the biggest criticisms of the flood of self-published

eBooks is the variable standard of editing without the filter of a publisher’s

editor to catch the flaws. I know this as it has happened to me.

In any case, while syntax is intricate,

it is relatively easy and - dare I say it? - it is fun. Every writer

should be the master of his or her own language. Grammar stands there alongside

originality, vision, vocabulary, narrative skill as a crucial tool for the

successful writer, whatever their approach to publishing.

Great Syntax at work

Ursula Le Guin also showcases the work of

the immaculate Scott Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby

‘Fitzgerald shows great skill in character and plot development

by employing surging breathless ragged, choppy sentences…’

“We went upstairs, through period

bedrooms swathed in rose and lavender silk and vivid with new flowers, through

dressing rooms and poolrooms and bathrooms, with sunken baths…”

“They were gone, without a word,

snapped out, made accidental, isolated, like ghosts, even from our

pity”

‘This was untrue. I am not even

faintly like a rose. She was only extemporizing, but a stirring warmth flowed

from her, as if her heart was trying to come out to you concealed in one of

those breathless, thrilling words. Then suddenly she threw her napkin on the

table and excused herself and went into the house.’

Look at these Fitzgerald

examples and turn to a few pages of your own manuscript. You will probably see

some good, effective sentences and paragraphs there and say to yourself ‘well

done!’

If not - being the all-powerful

writer – you can get to work and make some.

Happy

writing, happy editing

Wendy