Welcome

to Newsletter 18

Hello

again, dear reading and writing friends.

I’ve had to suspend my newsletter

for the time being as I have been very absorbed in putting the final touches to

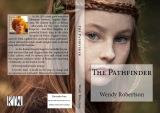

my new novel The

Pathfinder and working on a very special short

story that has been nagging me for two months.

I suppose the essence of this

present newsletter-message is that if you have an urgent, even obsessive need

to write, then write and write on – that more than any useful top or application

is at the core of the writing process.

So now my

novel The Pathfinder

is out

there

strutting

her stuff

(If you are inspired to read THE PATHFINDER you can obtain it HERE.

I hope you are entertained and enjoy it. Let me know.)

About the story:

The Pathfinder centres on the lives my heroine Elen, her song-smith brother Lleu and

their father Eddu a King of West Britain.

In 383 AD, myth and history tells us

of a truly great love story that blossoms between Magnus Maximus, the Roman

leader in Britain - afterwards for five years Roman Emperor - and Elen,

daughter of a powerful British king in the place we now call Wales. Magnus is

fascinated by Elen, a gifted Seer, healer and ‘pathfinder’ whose talented

ancestors made straight roads in Britain long before the Romans.

As the Roman Empire begins to crumble, the love and marriage between Elen and Magnus forge a link between the sophisticated creative

and trading Celtic culture (with its esoteric rites and rituals) and the

pragmatic military culture of Rome, now beginning to impose Christianity on the known world.

But while the story contains political and

historical themes it is the essentially personal story of Elen and Magnus Maximus

(called Macsen Wledig in the Welsh histories), Lleu, Elen's brother and Quintanius

Sixtus, Macsen’s friend.

And there are touches of Druidic magic...

|

Obtain Book |

Here is an extract from the story,

where Elen walks on fire at the Aclet Midsummer revels the day after she has

met the Roman commander by a water pool.

Excerpt from Chapter 14 Walking on Fire

[…]

Now Lleu’s voice rises in the air. His is not a prayer but a story. He declaims

a tale about the ancient power of fire that first came to our ancestors from Lugh

the sun God.

His tone deepens as he tells of great forces raised by Seers to defend our West Britain from the invaders. He names heroes who fought and seemed to win, then were defeated and slain in their thousands. He names great women who defied the enemy and threatened them with spells and bolts of fire spouting from their fingers. Then he tells how these heroic men and women of the highest council of the wise in the British West - – who in their honeycomb brains held ten thousand years of knowledge of the earth, the sky and everything in between; who were the nestlings of the Gods; who were the most significant of our people – all these great ones who were driven into the sea and slaughtered in their thousands.

His tone deepens as he tells of great forces raised by Seers to defend our West Britain from the invaders. He names heroes who fought and seemed to win, then were defeated and slain in their thousands. He names great women who defied the enemy and threatened them with spells and bolts of fire spouting from their fingers. Then he tells how these heroic men and women of the highest council of the wise in the British West - – who in their honeycomb brains held ten thousand years of knowledge of the earth, the sky and everything in between; who were the nestlings of the Gods; who were the most significant of our people – all these great ones who were driven into the sea and slaughtered in their thousands.

Now,

here on Aclet field, you can hear a feather land. You can sense all the people

there around the fire-pit straining not

to look at the visitors or the bright Roman standard floating above their heads.

They are tense, waiting.

‘But,

wait! Listen to me,’ Lleu goes on, ‘that fire still flickers around us even

today. We are still here. And in time

the British people will rise again and light their torches to drive the invader

from their lands for all time.’

Even

through my meditation I see that what Lleu is saying is forbidden: pure treason

against Caesar’s men. My blood chills. I

swear that if Lleu turned to the crowd this minute they would take up the fight

and demolish the invaders even here in their midst.

But

Lleu’s voice fades on the air and now an eerie silence fills it. My grandfather

and uncle’s faces are stern and Kynan and Gydyan have their hands on the hilt

of their swords. The soldier with the standard senses something, even though he

cannot understand Lleu’s words. His thick muscled arm tenses as he grasps his

standard more tightly. But the three of them, the Commander, the General and

the Procurator are standing easy, their faces neutral.

The

moment passes.

‘But

now in our day!’ Lleu cries on, ‘the flame that will achieve this miracle is

the flame of love, the warmth of peoples who see the eternal human spirit in

each other’s face and wish the other no harm.’

Kynan

and Gydyan relax and fold their arms across their broad chests again, to enjoy

the show. The soldier’s grasp on the standard loosens.

‘And

now listen to me!’ I jump into the silence. ‘My brother Lleu and I will walk

the fire to show to you…’

I scan the crowd, my glance stopping very briefly on the General and passing on ‘…to show you that we can make this miracle with our own human spirit and the help of the gods, sustained by our ancient power over fire and water, over the earth all around and the sky above and everything in between. In this action we show we are the British people and this we always will be. We are still here.’

At last the people in the crowd send up loud cheers and out of the corner of my eye I see the General smile slightly and say something to the man beside him, his Procurator.

I scan the crowd, my glance stopping very briefly on the General and passing on ‘…to show you that we can make this miracle with our own human spirit and the help of the gods, sustained by our ancient power over fire and water, over the earth all around and the sky above and everything in between. In this action we show we are the British people and this we always will be. We are still here.’

At last the people in the crowd send up loud cheers and out of the corner of my eye I see the General smile slightly and say something to the man beside him, his Procurator.

Lleu

raises his hand. I close my eyes and think of the statue of Olwen, of Arianrhod

in the centre of the pool in my father’s house. Cool holy water. This is what I have been taught. Then I raise

my hand and, side by side, Lleu and I begin, steady step by steady step, to

walk on fire. We do not hurry. The crowd

breaks into great applause as finally we leap back onto the grass at the far

end. The old priest, still standing there at the end of the fire pit, waves his

staff across us and sings a blessing. I am filled with energy and delight and

smile broadly as I wave at the great circle of people standing here. Lleu holds

up his arms in a victory salute. The young stick fighters beat their sticks

against each other making a rattling rhythm. A pipes-man squeezes out a few

notes. Another man makes his elk horn pipe squeal.

Lleu

smiles and shushes the crowd. ‘Would any here like to walk the fire as do my

sister and I?’ He grins broadly at the chorus of groans.

The

General’s Procurator shakes his head and calls out in a gargled version of our

own language. ‘Only a fool would do such a thing, sir. My master here says that

you and your sister do indeed have a gift with fire.’ He pauses. ‘Although he

and I, of course, would question your history. […] ’

(If you are inspired to read the novel you can obtain it HERE.

I hope you are entertained and enjoy it. Let me know.)

Special

Note: On my blog (click HERE) have posted some reflections on the historical

novel in relation The Pathfinder.

This begins: ‘The notion of ‘The Historical Novel’ encompasses a very broad field,

from the lightest historical romance, through weapon-laden, bloke-ish

historical battle-fests, through stately home flowery historical flourishes,

through be-whiskered historical detective crime, through clunking,

information-heavy didactic dissertations on some historical period thinly

veiled in story.

And now and then there will be a

psychological literary time-set masterpiece which is all novel, with history

printed naturally through it with Blackpool through rock. (See Pat Barker and

Hilary Mantel) Read on HERE…